There are many different responses to the pressing ecological and human disasters that beset humanity in the new century. Protesters of globalization, whether peaceful or violent represent only some of the most vocal.

Differing perceptions of the ecological crises and the causes generate different responses. At the “shallow” end there is the short-term, superficial reformist approach such as many kinds of conservation and the “greening” of our major political parties and businesses. Some of the violent disruptions of the kind we have seen recently would also have to be considered superficial. At the “deep” end there are the long-term responses which involve a thoughtful critique of the dominant world-view and which involve changed behaviours in our daily lives that generate harmony with all that lives. Peaceful protests could fall into this category. While reforms and short-term responses are beneficial, there is a growing awareness that they are not enough. The roots of the problem, of which the environmental crisis is but a symptom, must be understood. Without this understanding, our actions will only exacerbate the problems. This deeper understanding, once cultivated, will inform our actions (or non-actions) by putting them on the firm foundation of being motivated by universal compassion, universal responsibility and wisdom.

Let’s explore further how Buddhist teachings can shed light on the various ecological and social disasters looming ahead, and how they might aid our responses to them.

The Dharma

The Dharma could be described as the “laws of nature” or things as they are. These teachings according to senior Tibetan teacher Tai Situ Pa “are a coherent and detailed description of perceived reality which clearly indicates moral codes regarding our relationships with all life forms and includes a strong sense of individual and social responsibility.” Prince Sidhartha took an ancient ayurvedic diagnostic tool usually applied to illness and then radically applied it to life itself. He was concerned, as are all modern people, with the deep existential questions such as “How can I live my life happily and beneficially in the midst of the difficulties and uncertainties of life?” He asked the essential questions: What is the sickness? What are the causes of the sickness? Is there a cure? What are the elements of the cure? The Buddha produced a startling and detailed analysis of all our ills and their causes as well as solutions to them. Like a doctor he diagnosed the greater illness and then offered the most comprehensive remedy.

The Four Noble Truths

His medicine was The Four Noble Truths. Dukkha (that which is to be known deeply), the causes of Dukkha (that which is to be let go of), the ending of Dukkha (that which is to be realised), and the paths to the ending of Dukkha (that which is to be cultivated). Buddhism has always adapted to the particular culture into which it has travelled, but in order for it to remain a living tradition in the 21st century and the emergent global consumer culture, it must address the existential questions that concern us today. While much of what causes people to suffer has not changed since the time of the Buddha – there is still birth, old age, sickness and death – new factors must be taken into account, such as the systemic ecological problems that have the potential to terminate forms of life. Looking closely at the First Noble Truth, The Truth of Suffering (that which is to be known deeply) we see that all beings in conditioned existence, from the largest to the smallest, from the most powerful to the weakest, seek happiness, peace, comfort and security. They do not wish to suffer and, holding their own life dear, do not wish to die. We also learn that all beings do not find permanent happiness, peace, comfort or security and do in fact suffer and die.

The First Noble Truth

The First Noble Truth is a bold statement of fact: there is suffering in conditioned existence and we must face the situation squarely before we can begin to deal with it. To try to escape from it, deny it, ignore it or indulge in despair is to miss what it can teach us about ourselves and our situation. Denial of a problem is a common occurrence, as any doctor or psychotherapist will tell you. This tendency to be in denial with respect to the ecological crisis is a major difficulty. Most people would rather not face the seriousness or magnitude of the situation, nor do they have much compelling exposure to it. Preferring to escape by endlessly distracting and entertaining themselves or even flatly denying the problem and their responsibility for it, they maintain a “business as usual” attitude. After the Titanic hit the iceberg people continued to dance, believing that the ship was unsinkable, despite the sensory evidence of disaster all around them! If such a dramatic example of changing circumstances can be ignored, imagine how easy it is to deny a problem when the more subtle changes and the suffering they cause happen at a much slower pace, often over generations! The Buddha stressed the urgency for change saying that the human situation is like a man whose house is on fire. What was true for the individual then is becoming increasingly true for our collective existence today.

The Second Noble Truth

Even a superficial investigation into the causes of the crisis, as called for by the Second Noble Truth, will reveal that the collective behaviour of humanity and the impact it is having on living systems is the cause. The Earth is under tremendous stress, and we are clearly overstepping the limits of her life support systems to cleanse and balance the pollution and preserve nature as we know it in all its beauty and diversity. Meanwhile the consumer society with its dire attendant social and ecological impact goes largely unquestioned and mostly unchallenged.

The Third Noble Truth

The Third Noble Truth reassures us that a cure is possible, that we can arrive at an awakened plenitude not only for ourselves but more importantly for all beings. As Tai Situ Pa put it, we can fully awaken to the “perfect embodiment of universal wisdom, great compassionate love and personal power to help whomsoever is open to that help.” So in our analysis of the ecological crisis we need to recognize that a cure to ecological ills is possible. Indeed in some ways this has already been revealed by the Gaia Hypothesis which states that the Earth is a self regulating mechanism which always tends towards balance and harmony. The problem is that Gaia may just harmonise humans right out of the picture! So from the human perspective we need to look at how we can live on the Earth in a way which will sustain and support all living systems. But by identifying ourselves more with Gaia, than as individual consumers, we will be less motivated by fear of our own impermanence as a species, and able to fully respond to the situation we face from a place of deep connectivity. Buddhism can be a big help in this regard because it trains us in a habitual attitude of reverence towards all life. The teachings counsel us that we are not really separate from all beings and that the happiness we all seek lies, ultimately, in the happiness of all beings.

The Fourth Noble Truth

This is the Fourth Noble Truth in its essence: the path that must be cultivated. By training our minds in the six paramitas–or perfections–our being literally becomes the path, and all our actions spontaneously shift from being part of the problem to being part of the solution.

The first of the paramitas is generosity, which can also be translated as liberality or openness. This has many aspects to it but can involve the giving of resources, shelter, comfort, space, help, and so on, at a very practical and physical level. It can also be the willingness to “hear the cries of the world” and to respond with wisdom and compassion. Ultimately it is the recognition that one is not a separate “skin enclosed ego”, that there is no inherent “self” or “other”, no “giver”, no “gift” and “no one who receives”.

The second paramita, right conduct or ethics, is not to kill, cheat or steal, to avoid unwholesome actions and to develop wholesome attitudes. Ultimately it is to practice restraining selfishness and to find positive ways in which to support the welfare of all sentient beings. Right livelihood is a key aspect of this. In his book “Small is Beautiful,” E.F.Schumacher said that “Buddhist economics must be very different from the economics of modern materialism, since the Buddhist sees the essence of civilization not in a multiplication of wants, but in the purification of the human character”. Right conduct means non-involvement with those activities which are contributing to the suffering of the world. They require one “to live simply so that others might simply live!” Such a lifestyle would be, as Bill Devall said, “simple in means but rich in ends.” Although we would consume less, we would be happier knowing that our lives are in harmony with all living systems.

The third paramita is forbearance which is also described as patience- the opposite of anger. Ultimately it is to have more patience than the mountains and rivers themselves, indeed of Gaia herself. It is to have the patience of the Dharmakaya. The problems we face are vast, endless, complex, daunting – without patience, the game is up before it begins.

The fourth paramita counsels us to be strenuous, energetic, and persevering in our efforts. It is one thing to overcome our own denial, take responsibility for the problems, and become part of the solution. It continues to be challenging to live in a society where most people are clearly not doing this.

The fifth paramita highlights the practice of meditation so that we may attain concentration and oneness in order to serve all beings (aka our true self). It involves perfecting a stable, peaceful mind that is able to concentrate and develop penetrating insight. Thus we can begin to free ourselves from the tendency of the mind to become scattered through the push and pull of craving and aversion and take rest in equanimity. From this firm foundation of a peaceful mind we are able to investigate all the other mental states in ourselves and others so that we can free ourselves from the suffering of conditioned existence.

The Prajna paramita, or sixth paramita is our ability to rest in this wisdom, and in so doing, give the benefit to others. Just as a smile is infectious, and causes delight in others, so, much more powerfully, our wisdom and compassion shines like a warm and tender light on those around us, and our very being becomes a gift to others. The tremendously powerful delusions that keep us locked into a destructive way of life and produce great suffering individually and globally are supported by social structures and institutions based on values that are inimical to sustainable living. Beliefs in ideas such as the existence of value free (objective) knowledge, unlimited progress, and growth coupled with an attachment to individual freedom without corresponding responsibilities have eroded the moral values of our ancestral religions.

Secular society gropes for values with which to deal with the maze of moral problems confronting it. Buddhism is favourably placed to offer tools for transformation to a secular society because it does not rely on belief but rather on experience gained from inquiry and insight. The darker it gets the more brightly the light shines. I once asked Ringu Tulku Rinpoche how to deal with the enormity of what we may be facing. His simple answer impressed me deeply. If you do your best and the situation is turned around then that is good and there will be good fruits of those actions. But, he said, if you do your best and the situation is not turned around then that is still good and there will still be good fruits of those actions. We will never know if it is enough. Motivation and intention is everything. The outcome is out of our hands.

by Colin Moore, West Wing, Sharpham

Colin R. Moore initially came across Buddhist Teachings on “no-self” whilst studying Psychology at the University of Bangor, North Wales in the late seventies. Since then he has studied and practised in all the main traditions of Buddhism though his main teachers have come from the Tibetan Tradition. He has lived in a number of Buddhist Communities for around 15 years including 4 years at Samye Ling, a year at Gaia House and nearly a decade at Sharpham both in the Sharpham North Buddhist Community and Sharpham College for Buddhist Studies and Contemporary Enquiry.

He has a BA Honours degree in Psychology and a post graduate qualification which includes counselling and guidance from University College of North Wales, Bangor. He also has a Certificate in Advanced Counselling Skills from Plymouth University and has given counselling at The Barn Rural Retreat and at a Family Unit with the NHS. He is a qualified Hypnotherapist and Past Life Regression Therapist.

He hosts a regular Gaia House sitting group and teaches meditation and aspects of Buddhism at the Golden Buddha Centre, in Totnes, Devon UK, where he lives with his wife and son.

He has been practising and teaching meditation and mindfulness for many years and has taught at Sharpham College for Buddhist Studies and Contemporary Enquiry where he was a student and co-manager of the College for four years. He has also taught at Samye Ling Tibetan Monastery where he lived and trained for four years, The Barn, (a meditation retreat centre) and The King’s Fund (an independent charity working to improve health and health care in England).

He is the chairperson of Rigul Trust – a charity which provides health care, education & poverty relief to Tibetan refugees in India and for people who live in remote areas of Tibet such as Rigul. For more information please go to www.clearlightmind.co.uk

Article previously published by Parallax Press in: “Mindfulness in the Marketplace“, in 2002

Kindly contributed to Zen Moments by the author.

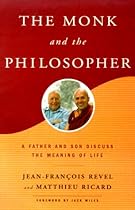

The Monk and the Philosopher: A Father and Son Discuss the Meaning of Life

By Jean-Francois Revel & Matthieu Ricard

![]() “Atheist, humanist father and Buddhist monk son hold a dialogue”,

“Atheist, humanist father and Buddhist monk son hold a dialogue”,

“The Monk and the Philosopher is a dialogue between a father who is an authority on Western philosophy (one of his books is entitled, From Thales to Kant) and a son who in his twenties took a doctorate in molecular biology at the Institut Pasteur and later became a monk in the Tibetan Buddhist Tradition.

From the very first exchange between father and son the book provides a surprising jolt of energy and clarity to the reader. Unnecessary things weighing on the mind fall away and one is welcomed into an invigorating world of essentials. The company of these two first rate minds, narrating the experiences of life that led them to the conclusions they hold – atheist humanism versus the view on the path toward Buddhist enlightenment, raises one’s own capacity for “the examined life” that Socrates considered the only kind “worth living,” and makes one feel the thrill of the mind working as a powerful instrument capable of cutting through sloth, avoidance and fuzziness to arrive at the threshold of a new awareness. (Like Keats, “Then felt I like some watcher of the skies when a new planet swims into his ken”).” Amazon customer Book Review

Wise and inspiring… good words for when doing the “right” thing seems in vain.

interesting flip flop of logic, and definitely a keeper to treasure…